- Home

- Declan Lynch

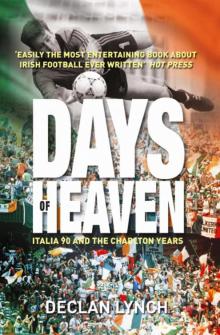

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven Read online

Contents

Cover

Title page

Introduction

1. Teenage Kicks

2. The Phone in the Hall

3. The Re-unification of Ireland

4. Ten Great England Defeats

5. Sometimes You Just Can’t Make it On Your Own

6. This Was Not a Football Match

7. Red Red Wine

8. A Sophisticated and Responsive Regulatory Environment

9. The Bono Story

10. Summer Nights

11. Euphoric Recall

12. The Shame

13. Against the Run of Play

14. Same Again Please

15. Outside, it’s Latin America

16. Drinking it all In

17. No Regrets

18. The Fat Man Sings

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

INTRODUCTION

When it was suggested to me that I write about my recollections of the Charlton years, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Italia 90, my thoughts naturally turned to a scene in a toilet in New York City.

It was a Sunday afternoon in June 1988 and the toilet was in a bar on 7th Avenue called Mulligan’s, which, by an extraordinarily happy accident, was also the name of the pub on Poolbeg Street in Dublin where I was doing much of my drinking back home — oh, how I laughed as I supped another glass of Schlitz and marvelled at a world which could contain such coincidences.

But then it had been a weekend of marvels.

I had been sent to New York to do a feature on Christy Moore for the Sunday Independent, for whom I had just started to write, mainly about Irish show-business personalities — the first was Hal Roach, then there was Sonny Knowles, so it must have seemed logical at the time to move on to Christy Moore. A lot of things seemed logical then, which do not necessarily seem logical now.

And this would not be the usual 800-word profile. It would be a special four-page glossy pull-out, illustrated with pictures of Christy stretching back to his childhood, to mark not just the life and times of the greatest living Irishman, but the fact that he was in New York to play the Carnegie Hall.

This was big stuff. Big enough for me to be accompanied by one Donal Doherty, an Independent photographer of renown, the sort of crack lensman you can still see on RTÉ’s Reeling In The Years, taking pictures of Charlie Haughey in the throes of some nightmarish Fianna Fáil heave. A man who had been a witness to various national traumas, which perhaps helps to explain why he was happy to be in New York on this particular weekend.

Because back in the old world, on the day after Christy played Carnegie Hall, the Republic of Ireland would be playing England in Stuttgart in the first game of Euro 88. Which was big stuff, too. And which will eventually bring us back to that scene in the toilet of Mulligan’s of 7th Avenue.

But first I should mention that we flew to New York via Heathrow, where we saw George Best. He was catching a flight to America, too. Perhaps it was just coincidence that the most gifted player ever to come from our island needed to be on another continent, perhaps even another planet, on the weekend that the Boys In Green were stepping on to football’s main stage. But at that moment I thought, it must be a great life George has, heading off to California unencumbered, whenever he feels like it, while the likes of me and the crack lensman are lugging our kit through the airport, the fear rising within us that we are going to miss our flight and miss all that big stuff. Airport security made Doherty empty out every roll of film he had in his large box of photographic tricks while the plane was revving up and seemingly certain to go without us. Ireland, lest we forget, was a world leader in terrorism at that time.

Even though it was general knowledge that he was an alcoholic, I did not know enough about alcoholism then to come to the more likely conclusion, that George was probably not sauntering off to some rendezvous on the West Coast without a care in the world, but was almost certainly boarding a flight for god-knows-where, with about ten dollars in his pocket and nothing else left in the world except the clothes that he wore and the inescapable fact that he was still George Best. Nor did I understand at any meaningful level that the Republic’s best-loved footballer, on whom we would perhaps be depending most in Stuttgart, the great Paul McGrath, was himself very far gone down that line. In fact, I did not even know enough about alcoholism then to know that I was getting a touch of it myself.

But I thought I knew about it. I was planning to raise the issue with Christy Moore when I sat down with him in some hotel room in New York — if we ever got there, which, as the Heathrow security men emptied the 54th tube of Donal’s film out onto the counter, seemed unlikely.

Christy at the time was one of the few famous Irishmen who had spoken openly about his tragic love affair with the bottle, and indeed had written a song about it, ‘Delirium Tremens’.

Yes, I would be asking him about that.

Not that this flood of recollections will be all about drink, by any means. But I sense that most readers, being honest, would have to agree that it must be at least partly about drink. That when they look back on those days, on Euro 88 and Italia 90 and the rest of what we call the Charlton era, it certainly wasn’t all about football. It was an overwhelming combination of so many things, a journey the like of which we had never made before, and all we know for sure, is that very few of us made it entirely sober.

But we got to New York anyway, the photographer and I.

We got to the Sheraton Hotel on the Friday night and soon I was in Mulligan’s bar on 7th Avenue, having a beer and watching a baseball game on the TV. And then the lads from the Gate Theatre arrived in.

In what now seems like some sort of a montage of the emerging Irish nation, the Gate Theatre was on Broadway with its production of Juno and the Paycock, directed by Joe Dowling, starring Donal McCann and John Kavanagh, on the weekend that Christy Moore would play Carnegie Hall and the Republic would play England in Stuttgart.

Interestingly, though we had been living through a troubled time in Ireland, we were still capable of sending high-class stuff to America, despite it all, perhaps because of it all. Juno was great, but no doubt it was happening at least partly because of its continuing relevance to ‘the situation’, the fact that there was still an IRA, capable of an atrocity such as the Enniskillen bombing, little more than six months before.

I think it was the actor Donagh Deeney, who was playing The Furniture Removal Man in Juno, who brought me into the company that night in Mulligan’s bar. Maybe it just happened by that ancient process of recognition that always draws Paddy to Paddy, on foreign soil.

I can’t remember if Joe Savino was there. Joe was playing Johnny Boyle in Juno. From the days when he sang in a rock ’n’ roll band, I had run into Joe on many occasions in my life, almost always in bars, and almost always when, by some unhappy accident, I had been drinking more than he. Over the years, I must have talked more shit to Joe than to most people. Which means that a fog of guilt and denial descends upon me whenever I think of him.

But if he wasn’t there, he should have been.

We were all so excited about everything. We were so excited to be in New York; we were particularly excited to be in a bar in New York with so much to look forward to, be it Christy at the Carnegie Hall or Juno, which was starting its previews the following Wednesday in the John Golden Theatre, or Ireland playing England.

Not that we were looking forward to Ireland playing England in the same way that we were looking forward to the other stuff.

Because, as well as excitement, there was also a deep fear in our hearts, as we faced into that battle. A fear that Jack’s t

eam might be no good, after all, and that they would get beaten by England, not just 2-0 or something vaguely respectable, but beaten badly. Beaten out the door.

As we proceed with this thing, we will examine this fatalistic streak in the Irish character, and how the events of the Charlton years challenged us to look at ourselves anew in this regard. To see ourselves as people who did not always need to be afraid of making eejits out of ourselves in the international arena.

But on this Friday night in Mulligan’s of New York, we were still on the cusp of all that. We were somewhat astonished to be at Euro 88 at all, but we still harboured that fear that on Sunday we would be found out, in the most disgraceful way.

Yes, these men who were talented enough and ambitious enough and self-confident enough to be standing on the Broadway stage alongside your Donal McCanns and your John Kavanaghs and your Maureen Potters, essaying the work of O’Casey in front of the most brutal critics of the New York theatre, were not immune to these old, old fears.

Elsewhere in the city, during that Broadway run, my friend Philip Chevron of the Radiators and The Pogues would be having a night off from Poguetry in order to give the town a new lick of paint with said Maureen Potter. And he believes that fellow Pogue, Terry Woods headed off into the Manhattan night with his buddy Donal McCann. Chevron also believes he drank with the actor Mick Egan, who played the Sewing Machine Vendor, in Juno. And Shane MacGowan was out there too, doing what Shane does, in New York.

And all of these Irishmen and women, even the most illustrious of them, at the peak of their powers, would have had their moments when they feared chaos on an unprecedented scale in Stuttgart. Chaos, and ultimately catastrophe, for the Republic.

There was also the lesser fear that most of us here in New York on this weekend wouldn’t actually see the match. Many of us, in fact, were secretly relieved that we wouldn’t see it, that we would be spared the truth being shoved in our faces.

It must be remembered that even in America back then, there were few big screens in bars, and even fewer showing ‘soccer’ matches. There was also the time difference which meant that even if the company at the Gate could commandeer some bar in Queens or wherever, the match would be happening on Sunday morning, New York time, which effectively ruled out myself and the photographer, who were due to fly back on the Sunday afternoon. And even if we somehow found a bar with a TV showing soccer on ESPN and a very fast car, we were haunted by the certainty that the snapper’s suitcase would be emptied out and inspected for about two hours on the way back.

And that would be too much — that, on top of some terrible slaughter.

——

But the Furniture Removal Man and the other guys in Mulligan’s were quietly confident that they would actually see the match — Donal McCann had sussed out a place, apparently. Or not, as the case may be.

That’s Donal, who joins Christy, Bestie, McGrath, Chevron and arguably Charles Haughey as the sixth alcoholic, not including the author, to appear so far in this narrative.

And Shane MacGowan is in a category of his own.

Though of course, these men had many other strings to their bows.

——

Christy was generous with his time the next day, his driver taking us to various New York settings like Washington Square Park, so that Doherty could take his pictures. Looking ten years younger than he had looked ten years previously, Christy talked about how he had given up the drink and taken up a macrobiotic diet. He had loved butter almost as fiercely as he had loved porter. Now he had become just as fond of carrot juice. Which perhaps accounted for his calmness on this day when he would be playing Carnegie Hall.

He would also speak of his ultimate disillusion with the republican movement after Enniskillen. Which was about time for him, though he got there in the end.

Christy was interested in a book I was reading about Henry Ford, the supreme achiever of the Irish diaspora. We were all interested in the photographer’s epic endeavour to buy one of those new car-phone things at the right price from a shop run by a bunch of Latinos, a car-phone thing in New York being fantastically cheaper than a car-phone thing in Ireland.

‘My girlfriend comes from Ireland,’ the shop owner lied, thinking this might tip the balance his way at a crucial stage of the negotiations, which would ultimately prove fruitless. ‘She is from County Bray.’

Christy’s was a tight operation, essentially himself, his deeply intelligent manager, former showband singer Mattie Fox, and a sound man. It seemed only right that Time magazine carried a small feature about him on the occasion of his visit to America, placing Christy in an international context of timeless roots music. We had come to expect nothing less from an Irish artist of this stature — by now U2 had already sold about ten million copies of The Joshua Tree, the Pogues had produced ‘Fairytale of New York’, the film My Left Foot was about to win two Oscars, and Sinead O’Connor was at that stage when, as they say, she could be anything.

But still we could hardly face Ireland v England in Stuttgart without a recurring sense of dread throbbing away in our guts. Ah, there is a deep restlessness in the soul of Paddy, and sure enough it could be seen and heard in snatches in the vicinity of Carnegie Hall that evening.

And let me clarify at the outset that when I refer to Paddy, I am not necessarily excluding myself. Like Afro-Americans with the n-word, I feel it is all right for Paddy to speak of Paddy, because he is himself Paddy, so he is speaking with love and understanding.

There were some Americans in the hall that night — the serious musicologist types who had been reading Time magazine — but this was a night for Paddy to be among his own kind and to let himself go. So many of the voices were clearly and ostentatiously from the counties of Ireland that it made a visit to the Gents sound weirdly like some flashback to the dancehall days when the lads would be supping from naggins of whiskey before heading back to the hall to take on the women. Rowdy lads would be reminded by more sensible lads that they needed to behave themselves, to remember that they weren’t at home any more.

This form of peer pressure was one which we were starting to see being enforced across the continent of Europe, too, Paddy on Paddy. In the era of football hooliganism, reporters covering Euro 88 would marvel at the way that the Irish would police themselves, how an errant fan with maybe a few beers on him, trying to steal a chocolate muffin from a display counter, would be chastised by his buddies, all quipping good-naturedly.

Back in the grand environs of Carnegie Hall, you could sense there would be no trouble either from Paddy, even from the most vulnerable of us, the alcoholics who would be out in force tonight, hailing Christy the lost leader.

This new wave of self-policing, even of personal responsibility, might have been partly due to the ever-present danger of attracting too much attention to yourself, as an undocumented alien. But there seemed to be a co-ordinated effort on the part of all Paddies everywhere to behave ourselves, now that we were going places. And more importantly, to be seen to be behaving ourselves. And even more importantly, for Paddy to be seen to be behaving himself better than John Bull.

Yes, we were going places — tonight we would celebrate our national bard at the most storied Hall in the most cultured city on earth, tomorrow we would also celebrate, win, lose or draw.

Except we knew that we wouldn’t win.

And we knew that we wouldn’t draw.

And we would have to deal with that, in the only way we knew how.

Did I feel any guilt, that I would not be witnessing this defining event in our island story? Not even a twinge, to tell you the truth. In the matter of the Republic of Ireland and of football in Ireland in general, I had paid my dues. My father Frank, who had been involved in football in Athlone all his life, was taking me to see the Republic playing in Dalymount when it would not be unusual to see Eamon Dunphy out there on the park.

But I don’t propose to list my full football credentials here — suffice to say that on this day, I fe

lt a bit like the wise peasant who plants the seed, unconcerned that he may not see the harvest. ‘My work is done’, I thought, as I dropped into Mulligan’s on the Sunday for a few more beers for the road.

I even felt some vague disdain for the hordes beyond in Ireland and in Germany, wondering where they had been on a night a long time ago, in 1981, when a few of us from the Hot Press magazine had to persuade the barman in a Mount Street pub to get the telly going in a quiet corner of the lounge so that we could watch Belgium beating us 1-0 in the pouring rain, the thunder and lightning in Brussels, denying us qualification for the 1982 World Cup with a late, horribly illegal goal.

It was such nights which had convinced Paddy that success was not for him. That there was nothing inappropriate or unreasonable in his mounting dread of what might be happening in Stuttgart ... what might already have happened in Stuttgart.

Yes, it would be over now, I thought, as I had another one for the road. In a world which had yet to discover the need for everyone to be constantly informed about everything as soon as it happens, in a country which regarded soccer as a girl’s game, in a time before texting, you just resigned yourself to finding out about things as best you could — especially if part of you didn’t want to find out.

——

So it was that I went to the toilet in Mulligan’s bar, where I encountered the actor Joe Savino — Johnny Boyle in Juno. It felt surreal then, and it still has shades of the Twilight Zone, because normally I would be running into Joe in Larry Tobin’s of Duke Street. Suddenly, it seemed that the world was no longer such a big place, for Paddy.

— The score?

— England won.

— Oh fuck.

— They won 7-2.

I believed him, of course.

No Irishman would have disbelieved him, at that time.

— They won 7-2.

— Of course they did.

At some stage Joe took pity on me. As a football man, with a natural inclination towards the truth, he could not let such a lie stand. Ireland had won 1-0.

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven