- Home

- Declan Lynch

Days of Heaven Page 14

Days of Heaven Read online

Page 14

Of course it captivated viewers from the start and sent Pavarotti to Number 2 in the UK charts (‘World in Motion’ was at Number 1). And more than this, it gave the impression that it was Pavarotti who had caught a break here, that his art was being honoured by its association with the great art of football, and not the other way round — an impression which Pavarotti, to his credit, appeared to endorse.

So the BBC opening sequence had the fat man singing, along with pictures of the opera and of nymphettes dancing around the globe and then the true art, images of Pele punching the air to celebrate his goal in the World Cup Final in 1970, and of Johan Cruyff giving some unfortunate full-back twisted blood, and of Maradona hurdling a tackle, and ... and there’s Ronnie Whelan, after scoring against the USSR.

We were there, appearing in the same movie as those guys. It had been confirmed by the BBC itself.

The sequence finished with the famous celebration by Marco Tardelli, scorer of the third goal for Italy in their 3-1 win over Germany in the Final of 1982. Running towards the touchline, his arms spread wide, shaking his head from side to side as if to savour all the incandescence of the moment, he is a vision of male ecstasy out of the Renaissance. The same Tardelli is now Assistant Manager of the Republic of Ireland.

Des Lynam was the BBC anchorman, still representing its urbane traditions in his own way, before he moved to ITV and — as always happened by some mysterious law of TV nature — lost his aura overnight by the mere fact of moving from the Corporation to the ‘commercial’ outfit.

The fever was upon us now.

Italy beat Austria 1-0 in the Stadio Olimpico on the Saturday night, generating an atmosphere in Rome which they would try to maintain throughout the tournament, a succession of luminous football nights which would convince the world that all World Cups should be held in Italy.

We did not need any convincing.

The winning goal was scored late in the game by the substitute, one Salvatore (Totò) Schillaci. He had not started the game, yet he looked like a star, with all these stereotypical Italian qualities of brio and braggadoccio.

And we were playing in this thing, on Monday.

We kept hearing of men who, swept away with the excitement, abandoned all their responsibilities and borrowed money under false pretences from the Credit Union to go to Italy. And it was always the Credit Union, not American Express or Mastercard — Paddy had yet to discover the magic of plastic. One can only surmise that the Credit Unions of Ireland at the time were staffed with unworldly people, who were unable to make the connection between this wave of borrowing and the amount of money a man might need to get to Italy and to drink wildly for about ten days. And perhaps even to come back.

We learned something then, about the extent of the black economy. And about the resourcefulness of the people when their country needed them.

In Roddy Doyle’s novel The Van, the unemployed Jimmy Rabbitte Snr and his best friend Bimbo become entrepreneurs during Italia 90, when Bimbo buys a broken-down chip van. There would be a great demand for fish and chips and batterburgers and chips and spice burgers and chips and breast of chicken and chips and curry sauce at this time. And Italia 90 would be a constant source of drunken banter with all the Italian-Irish chip-shop proprietors.

People who had no money, found money. They would sell a leather jacket. They would bring a bunch of albums to Freebird Records on Grafton Street or to the Basement Record and Tape Exchange on Bachelors Walk. They would sell a tumble drier or a cow.

But there was also a growing belief at home that if you went to Italy for the World Cup, you might miss it.

We got it into our heads that there should be a buffet, with cold cuts.

This being the occasion of Ireland’s first ever appearance in the World Cup, we felt that something special was needed, some gesture on our part, some effort to eat. Maybe we were trying to maintain a façade of civilisation in an increasingly primitive environment, but we probably just liked saying ‘cold cuts’, after hearing it in some movie. And it sounded a bit more Mediterranean than ham. Given the intensity of the night’s promise, it had a pleasantly ludicrous ring to it: ‘cold cuts’.

The plan was, Arthur Mathews and I would go to Liam’s flat, the old place on Crosthwaite Park, and there we would partake of cold cuts, but mostly of cold beer and then we would watch whatever awaited us down there in Cagliari. Which we guessed might remove any appetite we had for cold cuts, for ham, salami, chorizo, German sausage, or food of any kind.

We guessed right.

But to prepare our palates for it, Arthur and I began the build-up in the Purty Kitchen in Dun Laoghaire, where the afternoon match was being shown on the television — the big screen was up on the next floor, awaiting the evening crowd.

The afternoon match was Scotland v Costa Rica, which we suspected might provide us with just about the perfect pre-match entertainment, and which didn’t disappoint us in any way. In fact, Scotland exceeded all our expectations by losing 0-1 to Costa Rica, a result that would help Costa Rica into the last 16. It was such a comfort to know that whatever happened to us in Cagliari, there was always someone worse off than us, a nation of chronically unfortunate men who would be doomed forever to watch their team doing things like this, losing to Costa Rica and then beating Holland, or maybe Brazil, but too late to do them any good. Or scoring a late winner in Bulgaria to put someone else through.

The Fear was growing inside of us, but the combination of the drink and the Scots was helping us to cope. We loved those guys, for what they were giving us — a comic opera that had been running forever, and that will never close.

But we didn’t want to be joining them in it, on this night.

We were sick with The Fear as we walked to the other side of Dun Laoghaire to partake of the buffet. Or not as the case may be.

It was an admirable spread, in many ways, and many compliments were given to Liam but I can’t recall actually eating any of it. I was growing increasingly disillusioned with eating in general, at the time. Though I noted that Liam had added a bowl of these things called cherry tomatoes, which were only starting to become popular in Ireland at that time — he confessed that the aspect of the cherry tomato which most appealed to him was that it required no cooking of any kind, to be enjoyed. The celebrity chef had yet to become a significant figure in our society.

——

RTÉ didn’t have ‘Nessun Dorma’ but they were getting a feel for the ferocity of the people’s passion.

Football men have always said that the litmus test of football’s true popularity in Ireland is when GAA fixtures are cancelled because they clash with a big football match. Now concerts in Dublin by the likes of Mick Jagger and Prince were being cancelled, and RTÉ seemed to ‘get’ it, capturing the country’s mania for football by filming school kids all over the country, singing ‘Give It A Lash, Jack’ and ‘Olé Olé Olé’. For those of us who had sat in the International that day, waiting for Bulgaria to beat Scotland, or who had heard Éamonn MacThomáis declaring that Brian Boru was the only fella who could beat them Danes, this was a charming development. But we knew that the little ones couldn’t possibly understand the true gravity of the situation, as we watched them singing their songs with just a few minutes to go until kick-off.

Down at the RDS, a huge crowd was watching it on a suitably huge screen, and drinking a lot of lager. There was no doubt now that this was the biggest communal event since the visit of the Pope, or perhaps even the Eucharistic Congress of 1932, except now we had this thing called free will.

And the Leaving Cert was starting the following day. A few hundred yards away from Crosthwaite Park, Dion Fanning was watching Giles and Dunphy making their closing remarks, knowing that whatever the outcome, he would be going to an exam hall the following day for the first English paper, no doubt quipping good-naturedly that if he wasn’t defeated by the English this evening, he would certainly be defeated in the morning.

Fanning, who last appeared

in our narrative as a nine-year-old tearing up that picture of the hated referee Nazare, is now a friend and a colleague of Liam Mackey’s in the press box. But on the opening night of Italia 90 he had an even heavier burden to carry than the rest of us — on the morning after, no-one was going to ask us to discuss the character of Othello or to furnish written evidence that we had been reading Pride and Prejudice in the approved fashion. Juno and the Paycock was also on that year, though there is probably a tad more pleasure to be had getting drunk with the cast on Broadway, than composing an essay on O’Casey’s use of Hiberno-English in an exam hall.

Yes, there is always someone worse off than yourself.

But it didn’t feel like that when Gary Lineker scored for England after only eight minutes, somehow knocking a cross from Chris Waddle past Packie and finishing it with himself and Mick McCarthy in a heap in the net.

That was the coldest cut of all.

It was a horrible goal, scored in horrible weather, rain and thunder which we originally thought would have no effect on us: conditions were not good for football, but since we knew that Ireland had no intention of playing football anyway, we thought that if anything this would be to our advantage.

Now, it just reinforced our grief, thinking of how it would surely crush the spirits of the lads on the park and of course our brethren behind the cages on the terraces who had gone to Cagliari to show their Christian goodness and superiority to the ’ooligans. And who, we imagined, would now have had to listen to their hideous triumphalism, their cries of ‘No Surrender to the IRA’ and other finely crafted satirical barbs.

And yet when that goal went in, there was what Norman Mailer has called the strange sense of relief you feel when everything has turned to total catastrophe. Once the thing that is giving you The Fear has happened, and happened so soon, you know at least that you need no longer fear it.

But it didn’t look good.

We could no longer cheat reality, as we had cheated it in Stuttgart. Packie couldn’t keep the English out forever, and the ugliness of the goal seemed to suggest that the baleful gods were giving them something back for the miseries of Euro 88.

If there was any luck going around we felt it was the Irish that needed it, not an England team with John Barnes and Lineker and Gazza himself. So when the gods started doling it out to Gary Lineker, giving him perhaps the only goal of his career which he effectively chested into the net from several yards out, we wondered just how ugly this was going to get. And we knew we needed to score, at least once. Which confronted us with one of the more painful realities of Jack’s system, the fact that it wasn’t really about us scoring, it was about the other team not scoring.

High on the improbability of it all, we had been making the best of it and celebrating this idea of putting ’em under pressure, celebrating it indeed with a full studio production by Larry Mullen Junior. But even the lager-maddened throng at the RDS could not entirely escape the reality that some day we might need a goal, very badly. And that the best of way of scoring a goal, usually, is by playing something that resembles football.

Which we did not do.

It can even be argued that Jack invented a new code, a sort of Compromise Rules game which perfectly combined aspects of Gaelic football with a smattering of Association Football, again demonstrating Jack’s almost spooky compatibility with Paddy, how two dreams met. Aided by the back-pass rule which, in 1990, still allowed the ball to be kicked back to the keeper and the keeper to pick it up with his hands and to kick it up the park at his leisure, just like a Gaelic player, Jack had absolutely no problem with the notion that Packie Bonner might be our ‘playmaker’ — receiving the ball from the defenders and booting it as far away from his own goal as possible, hopefully towards an Irish player. But that wasn’t important — as long as it was up the other end, according to Jack, the other crowd wouldn’t be scoring.

But how were we to score?

Just as Jack’s brutal experiment seemed to be going down in the mud and the blood of Cagliari, just as we were facing the truth, asking ourselves how in the name of God we were going to get anything out of this game with Packie hoofing the ball up the park to no-one in particular, the answer came — from Packie hoofing the ball up the park to no-one in particular.

In this case the recipient happened to be a member of his own team, Kevin Sheedy, who mis-controlled it towards Steve McMahon of England, just on the edge of his own area. It would be a goal as horrible in its creation as the England goal, since it was essentially made by a player on each side losing the ball, and all as a consequence of Packie’s massive punt. Yet in execution it was beautiful.

In one instinctive and decisive movement, Sheedy had stolen it from McMahon and swept it with his educated left foot into the bottom right-hand corner of the net.

All of Ireland, and all Irish people all around the world, went mad with joy.

In Crosthwaite Park, we jumped around the room, roaring savagely.

At the RDS they would be seen erupting in drunken ecstasy, both in still photographs and in RTÉ pictures which captured this instant transformation from sombreness to crazy jubilation.

People who did not know one another hugged and kissed. Men told other men that they loved them.

Arthur appeared to be prostrate, in a quasi-Islamic posture, as if giving thanks to a personal God. At some point in the mêlée, my cigarette was extinguished and it was only when smoke was later seen billowing from the couch that we realised where the lit end had gone. Not that we cared about burning couches. Even if it was the one that Bono had sat on, telling old showband stories.

On the pitch, the reaction of Steve Staunton seemed especially demented, perhaps the Dundalk man in him responding with that extra bit of fervour to the blow which had been struck against the old enemy.

But there was still about 20 minutes to go. I can’t recall any thought in our heads other than the thought of hanging on somehow. If the result stayed as it was, we would ‘win’. It was not for us to be playing for an actual win at this stage, it was down to England to chase the victory which was the least expected of them by their unhappy followers and their demented newspapermen.

We were looking for a different sort of victory. One that would be celebrated with as much fervour as the Miracle of Stuttgart, though the dynamic was somewhat different. In Stuttgart we had been hanging on somehow for almost the entire match, whereas in Cagliari we had created a new narrative, one of redemption, of rescuing ourselves from the darkest fate imaginable. In Stuttgart the Fear that England might score had been total and undiluted until the final whistle; in Cagliari that particular Fear had gone early doors and we had moved into a new realm of dread from which we were rescued so fabulously by the Sheedy goal.

And now, of course, there was 20 minutes of a whole new form of dread to be endured. I recall dreading Gazza most of all, Gazza who seemed to be the only man in Sardinia on that night with any real interest in playing football and who was clearly capable of it too, which was especially worrying.

But we got away with it. And we felt that we were in good standing again with the baleful gods when the replay showed that Alan McLoughlin had been in an off-side position and that our goal might have been disallowed. Twelve years later, as he neared the end of his career with Forest Green Rovers, McLoughlin would tell Jon Henderson of The Observer that he knew he was offside: ‘I quickly wheeled away to the right, and it was only after I’d run about ten yards, when I saw the linesman had kept his flag down, that I knew I’d got away with it.’

Fifty-thousand replays later, he was still clearly offside. But the goal would still stand.

How many times has the average Irish person seen the replay of that goal? From the kick-out by Bonner to the joust between Sheedy and MacMahon, to the ball flashing past Peter Shilton and then the players messily celebrating and the Green Army going berserk on the terraces it takes about 20 seconds. How many hours of our lives have we spent looking at that 20 seconds, indulging

in what recovering alcoholics describe as ‘euphoric recall?’

It is an apt description in the circumstances, as so many of us happened to be drunk at the time.

So we are euphorically recalling the goal and we are also recalling being drunk and the whole country apparently being drunk along with us.

Dion Fanning, remarkably, was sober on the night, presumably due to that slight complication of the Leaving starting the following morning. So he has a clear memory of getting into his car after the match with his brother Evan and driving from Dun Laoghaire into Dublin, blowing the horn.

He believes he was the first person in Dun Laoghaire, maybe the first person in Dublin to start blowing the horn, or at least he didn’t hear anyone else blowing the horn until he started doing it himself. Maybe this was the horn we heard in Crosthwaite Park, one of many unfamiliar noises, the irresistible sound of people taking to the streets, the sound of fiesta.

Dion says the journey into town was unlike any we had known in this Republic, where men tended to blow their horns in delight only on their way to a wedding reception, fired up by the thrilling prospect of drinking for the rest of the day with a cast-iron excuse. With horns blaring and flags waving we might have been in some country where the people are unashamedly demonstrative, maybe somewhere in Latin America. But for the absence of indiscriminate gunfire, we might have been in Cameroon.

Such a night ...

——

And there was the promise of more, with qualification from Group F now looking almost certain. Having come through this terrifying trial, we could only see good things happening in our next match against Egypt on Sunday. And we felt it reasonable to assume that Egypt would be beaten by Holland in their opening match the following night and then beaten by England in the third match, what with England needing the points after what we’d done to them tonight.

As we slumped in Crosthwaite Park, elated and utterly exhausted, euphoric recall was heaped upon euphoric recall, the images of this night already assuming the status of sacred icons.

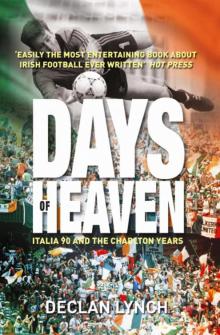

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven