- Home

- Declan Lynch

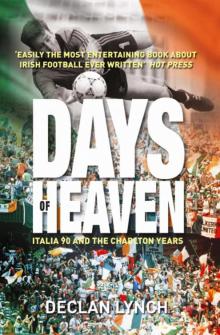

Days of Heaven Page 16

Days of Heaven Read online

Page 16

In his pre-match analysis, Eamon Dunphy had this vision: ‘This is for the whole country,’ he said, ‘And the team is a catalyst. The character of our people out there, the team ... they haven’t had one yellow card. And the way we’ve celebrated the whole thing is glorious and golden and it’s for every single person, all the kids, all the players, everybody’s involved and everybody’s made a contribution.’

But it was the post-match analysis that would hit the spot.

‘Anyone who sends a team out to play like that should be ashamed of themselves’, he said. ‘We know about the upside of Jack. We know how hard these lads work. We know about their courage. But football is a two-sided game, when you haven’t got the ball and when you have got the ball. When we got the ball we were cowardly, ducking out of taking responsibility.

‘I feel embarrassed for soccer, embarrassed for the country, embarrassed for all the good players, for our great tradition in soccer. This is nothing to do with the players who played today. That’s a good side. I feel embarrassed and ashamed of that performance, and we should be.’ And he threw his pen down, as if throwing down the gauntlet.

It was a challenge which would not be refused in the days to come, but in the Purty Loft, most of us were too depressed to be analysing Dunphy’s analysis. In fact everything he said, before and after, seemed accurately to reflect the feelings of the multitudes — we had plunged from a manic high to a manic low and a lot of us now had a lot of drink taken.

Ireland, at this moment, was in a bad place.

Eamon Dunphy lives in the moment. In a human being this can be disastrous, in a TV analyst it is a priceless gift. And it is a gift which belongs more in the grand tradition of showbusiness than that of journalism, in the conventional sense.

The journalist of the old school will usually have a checking mechanism, reminding him that he is being inconsistent. He can’t plunge from euphoria to revulsion in the style of Dunphy before and after Egypt, without feeling some need to explain, to declare in some mealy-mouthed fashion that he may appear to be contradicting himself, but he has been left with no option, due to this unfortunate and unexpected turn of events.

Dunphy doesn’t bother with that shit. Living in the moment, he calls it as he is feeling it in the moment. Which can sometimes lead to him apparently contradicting himself, in the course of a three-hour football special — indeed, it is not unknown for him to be feeling different about something at the end of a sentence than he felt when he was starting out.

But then most of us who are watching TV are living in the moment, too, and we have busy lives, so when he moves on, we move on with him.

In those days Dunphy was also writing a column for the Sunday Independent, work which was compared by the journalist Sam Smyth to that of an opera singer — the articles were like arias, grand statements of high emotion, where the practitioner is front and centre and bursting with adrenaline, not sitting down in the dark in the front row scribbling into a notebook with the other critics, broken down by the tyranny of fact.

And while he had made his name in newspapers, originally with the Sunday Tribune, writing about football and about the wretchedness of the League of Ireland in particular, it was during this time with the Sunday Independent that Dunphy really found his voice. Instead of just writing about the serious business of football, he could be found offering his opinions on the more light-hearted and trashy aspects of Irish society such as politics and public service broadcasting.

Which in retrospect seems like a natural development, though at the time it took the Sunday Indo Editor Aengus Fanning to figure that one out. To decide that there was no law against football men writing about other aspects of the human condition, if they were able to do it.

There is also a complicated theory that the Sunday Indo became a great success at this time, not because it was championing the pluralist attitudes which were becoming general all over Ireland, or because it was implacably opposed to the IRA, or because gossip columnist Terry Keane was known to be having an affair with Charlie Haughey, or because the likes of Dunphy and Sam Smyth and Veronica Guerin and Colm Tóibín and Anthony Cronin were writing for it, but essentially because I had started to write for it.

It is a theory that you don’t hear too often, though it has at least one strong advocate — my mother.

And as for myself, I have always found working for the Sunday Indo about as uncomplicated as anything can be in this life.

There was a message for me one day in the Hot Press, that Aengus Fanning had called. I had heard of Aengus Fanning, but I wasn’t sure what he did exactly. A passing Jackie Hayden, General Manager of Hot Press, told me he was Editor of the Sunday Independent.

Aengus got back to me later, wondering if I’d be interested in working for the paper. I told him I would.

A few weeks later I answered the phone in the hall and it was Anne Harris, asking me to write an article about Hal Roach, which I assumed was to be written in whatever way I had been writing other articles for Hot Press or the Irish Press or whomever, because I couldn’t do it any other way.

So I did that — Dermot Morgan performed the highlights of Hal’s repertoire for me over the phone, in Hal’s voice — and I brought it in, and they then paid me more than anyone else had ever done. They were also exceptionally nice to me and they asked me straight away if there was anything else I wanted to do — still not very complicated, but it seemed to be working.

And yet there is this nostalgia now among media folk for the hungry years of Hot Press and Magill and In Dublin, many of whose contributors are now well known. We wonder how it all sort-of faded away when Ireland hit the big-time, how the fine young energies of the next generation got diverted into other things, where you might have the vague prospect of eventually making something approaching the average industrial wage. Because you wouldn’t start writing for these publications for the money: you were getting your big break and you were getting your opportunity to bring the government down on a monthly basis and you were getting free drink and free cocktail sausages and free triangular sandwiches, but you wouldn’t be getting rich any time soon.

And because we weren’t living in a money economy, as such, many of us never fully adjusted to the notion of actually getting paid a living wage for this thing we do. Most of us who started out in magazines at that time had no idea about what we could or should get paid.

John Waters recalls ‘haggling’ with Vincent Browne over a fee for a column about RTÉ daytime radio which he had been asked to do for the Sunday Tribune. Browne was adamant that he didn’t want any of Waters’ opinions in this column, none whatsoever, not even the vaguest suggestion of a point of view, he just wanted to be told what had been on the radio. Waters clearly couldn’t get his head around something so stultifying and he knew there would be a confrontation about something else, too, the difficult subject of money.

For days, he had steeled himself for the meeting. It had been suggested to him that you could actually make a bit of money at this journalism and John was determined not to sell himself short.

‘How much do you want to get paid for that?’ Browne said.

John summoned up all his courage. ‘I want fifty pounds a week’, he said.

Browne was horrified. ‘You can’t fucking work for fifty pounds a week,’ he said. ‘I’ll give you eighty to start and we’ll review it in a few weeks.’

Just like that, he had beaten him down.

We had no proper concept of money because we were still in a better place than we ever imagined we would be; we could never get it out of our heads that if we weren’t going over to London to interview Robbie Robertson, we would be playing a game of darts in some pub in the midlands, and we would be doing that, and nothing but that, for the rest of our lives. We still couldn’t quite figure out how this thing had happened to us.

‘It was all against the run of play’, Waters told me once. He reminded me that he was making his daily deliveries in a Hiace van in Castler

ea when Niall Stokes phoned him to enquire, not if he might fancy doing another review of Horslips somewhere out in the west, but if by any chance he might be available to fly out immediately to do a piece on Dire Straits in Paris.

‘We were innocent enough to be amazed by such things, but we never imagined that if our lives kept getting magically better in this way, we would acquire any power in the conventional sense, of being allowed to participate in the running of an institution’, Waters recalls. ‘Nothing belonged to us except the air, into which we could proclaim the things we loved and the things we hated — this is a great album, this is a shite album. The only power we had, is that we could say whatever we liked. And we felt we had the right to say whatever we liked, because we cared about these things, because they were important and because they had changed our lives.’

And evidently we regarded this as such a precious thing in itself, we thought that about fifty quid a week would cover the rest.

So when I was paid a three-figure sum for my first contribution to the Sunday Independent, I was shocked. Of course I was deliriously happy, and yet I also had this feeling of guilt — for all our rock ’n’ roll attitude, the young journalists of the 1980s could not get away from these ancient weaknesses, which had held Paddy back for so long.

I particularly recall that day on the third floor of the old Indo building on Middle Abbey Street, when I brought in the Hal Roach piece and Aengus went off to make us coffee, as Anne sat there trying to read my typed sheets about Hal, with the amendments written in biro — I had always assumed that the editors of national newspapers were the sort of men who would order coffee to be brought to them. I can only conclude that Aengus was making the coffee for us that day, because it was less complicated than getting someone else to do it.

——

The least complicated thing to do with Dunphy — and thus by far the best thing — was just to let him fire away. It was probably the polar opposite to the Charlton style of management, which would never have tolerated a soloist like Dunphy, let alone encouraged him and given him the reassurance that if he screwed it up, he would be supported — massive libel damages of three hundred grand to Proinsias de Rossa would back that up, baby!

But if the Sunday Indo had put him on the main stage, Dunphy’s post-match comments were about to put him where a man of his enthusiasms ultimately needs to be — front and centre. It was exhilarating, but it was also a very dangerous place for him, because Dunphy had stirred the mob instinct that is always latent in such a gathering of the multitudes.

There was an ornery mood across the land, in the aftermath of that horrible match in Palermo, and there was a need to direct that bad feeling towards something or somebody. We couldn’t really bring ourselves to direct it towards Jack and the lads, because this was not a search for the truth here, it was a need to rid ourselves of a world of bile.

So, in a text-book example of how the mob is aroused, Dunphy’s comments started to get twisted ever so slightly, and soon it was widely accepted as fact that he had declared that he was ashamed to be Irish.

At some level, the mob must have known that this was not what he’d said at all. But they weren’t being reasonable at this moment, they weren’t interested in nuances, they were looking for something to hate.

And anyway, what is wrong with being ashamed to be Irish, now and again? There is no country in the world which doesn’t have a few things to be ashamed about, and we, who had harboured the IRA and the Magdalene Laundries, can throw our hat into the ring with any of them.

But that is a rational assessment, and we were not in a rational frame of mind: we were seething, because this had been a supremely happy time, until now. These were the best days of our lives, and just when we had started to get carried away by the good of it all, we were hauled back and told we were no good and we’d be going home soon, probably in disgrace.

Not surprisingly, the first man to inform us of this was going to be a tad unpopular — especially if he was the same man who had been extolling the beauty of the moment at the start of the show.

In this great gathering, much had been made of the fact that our Italia 90 had spread way beyond football, bringing in the entire population of the country, which included a load of people who knew nothing about football.

Now, at this extremely tricky stage, we realised that not knowing about football could be something of a drawback, that too few of the folks knew enough about football, to know that football deals in the truth, that you can’t get away from the realities of scoring and letting in goals or not scoring at all, that the bottom line can’t be finessed and the result can’t be made to look any better by a PR company.

Giles and Dunphy had been educating us about the superior nature of football values for some time, but still we were finding it hard to take.

Football is not business or finance and it is not politics, where all that bullshit works, all the time. Which may help to explain why it seems so alien to so many of the panellists on Questions and Answers, who have thrived in that world of bullshit, and who simply can’t make the step up in class, to treat of more substantial matters.

But the fact that Dunphy was right about the performance against Egypt did not in any way placate the baying hordes. He could even be accused of being too lenient on Jack, of going on the attack only when the result went the wrong way, but in fairness to him, he had written about the ugly side. He had argued in the Sunday Indo that David O’Leary had been treated appallingly by Jack, who preferred the clearly inferior Mick McCarthy, for his own ideological reasons.

And there were times when Jack himself couldn’t hide the ugliness, most notably in comments quoted in Paul Rowan’s The Team That Jack Built, in which Jack describes why he picked an unusual team featuring Stapleton, Brady and Tony Galvin for a pre-World Cup warm-up game against Germany: ‘With Ireland, you see, they don’t give up their fuckin’ heroes easily, so you’ve really got to show ’em. If I don’t pick Liam to play or I don’t pick Kevin Moran to play or I don’t pick somebody who’s Irish and who’s been there a long time, they want to know why you don’t fuckin’ pick him to play. And you say, “Well, he’s too old, he’s not fast enough now. I want somebody who can do better for us in the years to come, and I’ve got to re-shape the side.” So what I did was, I put ’em on display. I had three of them — Liam, Frank and Tony Galvin — who were coming to the end of their time and I put ’em on display to the public.’

Stapleton ruined the display by scoring and generally playing very well, leaving Jack with virtually no option but to include him in the panel for Italia 90, a move which Jack would bitterly regret, telling Rowan that Stapleton had been a moaner and a pain in the arse to him.

But it was Brady’s last match for Ireland. Jack substituted him after half an hour and put on Townsend instead, a move which so infuriated Brady he resigned from international football, insisting that he had been humiliated by Jack, that he should at least have been substituted at half-time.

Ugly, ugly stuff, this ‘putting ’em on display’.

Still, we should probably be more forgiving about the things men say when they’re riled. I have learned that in people of talent, there is often a blind spot, or three or four blind spots — and that goes for Dunphy as well as for Jack.

So now that the ugly stuff wasn’t even working any more, we couldn’t find it in our hearts to turn on Jack, after all he had done for us. So we turned on Dunphy instead. When you’re living in a beautiful bubble, you just don’t want to know about that ugly stuff.

Italia 90 may have given us a foretaste of the Tiger, but not necessarily in the way that the corporate dudes claim, with their talk of ‘confidence’. Maybe the boom was most like the Charlton years in the sense that it was a bubble, maybe with less spontaneity than the original, but created by our desperate desire to be free of all that held us back, sustained by a degree of self-deception, a lot of talk about what a great people we are, a certain amount of borrowing and a lo

t of drinking. And while it worked for us for a long time, it also meant that we had to give up certain things that were part of our better nature, the way that we gave up Liam Brady and had very little use for Ronnie Whelan or David O’Leary.

It’s not that Paddy suddenly got good at everything some time in the mid-1990s, no more than we suddenly got good at football in 1987. If you recall, in the first pages of this book Paddy was on Broadway and at Carnegie Hall and selling shedloads of U2 albums, so we had always had a flair for what you might call the finer things of life. And you don’t end up on Broadway without ‘confidence’, you don’t end up at Carnegie Hall without knowing how to make a few quid either.

But perhaps the Charlton years showed us how to make the ugly stuff work for us as well. How to make money out of boybands and chick-lit and Irish dancing, the way we made our mark on the World Cup, doing it Jack’s way.

And not being ashamed of it.

Except perhaps, for a little while, one afternoon in Palermo.

Dunphy’s car was surrounded at the airport and it was rocked from side to side by a bunch of blackguards, with Dunphy inside it.

It was a very, very ugly scene.

But when they look back on it, even these renegades of the Green Army would have to concede that Dunphy was bringing something to the party, because a great story needs a few dark interludes, a few moments when disaster seems inevitable but is somehow averted. And we had had several of these during the England match alone, quite apart from this protracted agony-in-the-garden in the days before the last match of the Group, against Holland.

The climactic nature of this encounter had cranked everything up to a new level of madness. It was anticipated that the entire population of the country would be watching it, that you’d be able to walk down O’Connell Street on Thursday evening without meeting a soul, apart perhaps from the photographer who would be taking this unique picture of the main thoroughfare of a capital city, deserted — but who would take that photograph?

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven