- Home

- Declan Lynch

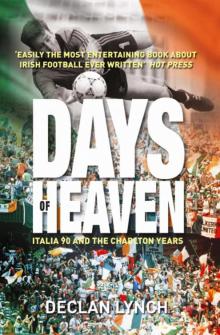

Days of Heaven Page 18

Days of Heaven Read online

Page 18

It is remarkable indeed, and perhaps a little troubling, just how insensitive we were to the sufferings of the Egyptians. As if they hadn’t suffered, too. Had they not been through war, within living memory? Were they not an ancient and venerable culture which had given nearly as much to human civilisation as we had? And even if they had given nothing, did they deserve to get knocked out of the World Cup by this sort of blackguardism?

Unfortunately, by asking these questions, the Egyptians would be mistaking us for people who gave a fuck.

So secure were we in our sense of victimhood, we could not feel their pain.

We could not feel any of it. Not a twinge. And even if I am starting to feel just a small pang of remorse, twenty years on, to cure it, all I have to do is think of that piece written by Paul Howard about his pursuit of the accursed Nazare, the referee who did us down in Brussels. All I have to do, is think of the nine-year-old Dion Fanning tearing out that picture of Nazare from the Sunday paper, and ripping it up in disgust.

So there was no point telling us that the hearts of the Egyptian people were crying, as they watched their World Cup being taken away from them in such a cruel fashion. And there was definitely no point in telling Dion Fanning, that he should feel bad about anything, as he made his way to a party to celebrate with a house full of other young people who were already wildly drunk. The Leaving was still on. But Fanning recalls he had ‘broken the back of it’ at this stage — if indeed it wasn’t already broken before that first English paper.

Arthur and Liam and I were getting a taxi from Dun Laoghaire into town, where we would be meeting Mr George Byrne in the Pink Elephant for drinks. Outside, it was Latin America, the horns blaring, flags flying out of cars, the ‘Olé-Olé’-ing and the ‘Give-It-A-Lash-Jack’-ing.

Unbelievably, there was still one more good thing to happen to us, one more break for us to catch. Tied on points and goal difference with Holland, we were awarded second place in the Group by the drawing of lots. Which meant that in the last 16, Holland got Germany.

All we had to do was to beat Romania.

‘I missed the World Cup,’ Con Houlihan mourned. ‘I went to Italy.’

During Italia 90, families sat down together and made what they believed were rational decisions to spend the money they had been saving for years for an extension to the house, on this holiday in Italy. I was particularly impressed by the story of a man who ‘bet’ that Ireland would finish second in the Group, booking cheap accommodation well in advance for his family in Genoa for a match in the last 16 that might never happen — sensible people, living on the edge for a while.

But mostly, it was as sensible as it can ever be when a bunch of drunk lads gets into a mini-bus outside their local pub in the centre of Dublin, and sets off for the World Cup. For all their cavalier attitude, they would be humbled by legends of men who opted for some extremely complicated sea-route, because they just liked the idea of sailing to Sardinia in an extremely dangerous boat. Or the guy from Limerick who flew there and back in a single-engine aircraft, allegedly made from little more than plywood.

And all this, to miss the World Cup.

But we would hear of the adventures of the Green Army, mainly through the radio reports of Nell McCafferty for the Pat Kenny show. As a rule, I am fiercely opposed to journalists who don’t know much about sport doing ‘colour pieces’, based on the flawed premise that they can bring a ‘fresh perspective’ to the occasion, can see things that maybe the more seasoned observers have stopped seeing. In fact, they usually end up seeing very little that is of any interest to anyone, because there is some essential aspect of sport that eludes them, an obsessional quality without which sport itself is meaningless.

A big football match is not like the Spring Show with a slightly more competitive edge. It is not an ‘occasion’ in the usual sense — there is too much at stake, for the faithful. Of course, a lot of people have never felt that obsession, that intensity, but Italia 90 gave them a taste of it, a sense of what some of us had been feeling for most of our lives. And when it was over, they would never really feel it again.

So on the whole I would prefer not to hear reports by people who are coming to it with this ‘fresh perspective’, but in the case of Nell, I would make an exception. Nell is a great reporter, who works best when she is mingling with folks, just hearing their confessions, as it were. And as the Irish made their way towards Genoa, she was able to bring a genuinely fresh perspective and to muse on the meaning of it all.

Nell wouldn’t see such an extraordinary journey in isolation from all the other extraordinary things that had been happening back home throughout the 1980s, all the sheer bloody unhappiness and unpleasantness which was now being purged on this weird odyssey. In particular she described what it meant for all these men and how they were behaving themselves so far away from home. Nell, the feminist, was impressed by a lot of what she saw, not least the fact that so few of them were screwing around, or even thinking about it. One fan, when in Rome and unable to find a hotel room, had had some sort of a sexual encounter with a Dutch woman in the catacombs. Happily married for five years, he felt the flagellations of guilt so well-known to Paddy in these situations, at home and abroad. And he went to Nell to confess. Seeing the state he was in, and the genuine agonies of conscience he was feeling, she told him to consider it a bonus and absolved him.

She noted that men who had never been on the continent before, were relishing the achievement of negotiating their way to Italy, and around Italy, and was particularly struck by one young man from one of the toughest parts of Dublin who had twelve different currencies in his possession, who had worked out a lot of things he never imagined he could work out and who broke away from the boys in Rome to take a trip to Pompeii, to broaden his mind.

Most memorable of all, were the scenes which reminded us that the Irish had no mobile phones then, that they really were on their own out there. So there would be a queue, a very long queue, outside a phone box. Mostly, they just wanted to tell the folks back home that they loved them.

At no other time, in Ireland or outside Ireland, have so many Irish people told other Irish people that they loved them. Paddy was liberated at this time, and not just by the drink. He had, after all, been drinking for quite a long time, without it coming to this. And in Italy with the heat and all the logistical issues, he couldn’t drink like he could at home.

But the Italia 90 campaign gave him a new sort of confidence in certain areas. He didn’t have to work out how to behave himself in front of all these foreigners. With the peer pressure and the reputation he had already garnered, he knew only one way to behave — he would behave well. That was all he needed to know. It could be reduced to a simple question and answer.

Q: How is he supposed to behave himself?

A: Well.

His normal levels of self-consciousness were heightened another few notches, but now he had these strong directions to guide him. To his antic disposition, was added a military discipline. And the mad uniform of the Green Army also gave him a certain camouflage, because it removed another area of doubt and confusion for Paddy, especially in a country such as Italy where they tend to be a bit on the stylish side. It meant he didn’t have to be worrying about how he looked to the discerning eye. He was wearing an eejit’s costume, which sent out the signal: this is an eejit’s costume. It’s not me.

It certain rare cases, of course, it might be an eejit’s costume, containing an eejit.

But how could anyone tell?

——

Back home, we were also living in a strange country, perhaps all the stranger because we hadn’t physically left the island. It felt as if we were living at altitude, as if all the best energies of the people directed towards the same cause had lightened the air itself.

We had come through these trials like the heroes of a medieval saga, and we were better people for it. What was the worst that could happen to us now? A big performance by Gheorghe Hagi, the Rom

anian captain, perhaps, but that was OK. We could live with Romania beating us, the same boys who used to come over here for ‘the bit of freedom and some decent food’.

And we could enjoy the rest of the World Cup, as we became more accustomed to the notion that we were part of this — no less than the trees and the stars, we had a right to be here.

We could savour the last-16 match between Germany and Holland in particular, knowing that it could have been us out there, trying to beat the Germans. We knew the joke that football is a game played with a round ball by two teams, each of which contains eleven players, and in the end the Germans win.

——

It was the eve of our match against Romania, and we were drinking it all in.

The Romanians did not have the aura of the Germans or the Dutch, to overpower us.

Dunphy was back from Italy, his reputation secure.

Whatever about the best supporters in the world, we have always had the best TV panellists in the world, in Giles and Dunphy.

In fact, with his first-rate mind, cutting to the essence of any proposition, sensing the unmistakeable waft of bullshit a million miles away, Giles is probably the best TV analyst pound for pound across all areas, from politics to the arts to his own discipline, the one that matters. And his presence on the panel at this time was given further gravitas by all he had done for Ireland in the bad years, as player and manager, and all that had been done to him.

Dunphy always deferred to Giles as the better player and the better man, but Dunphy was now on a personal high, and loving it, baby!

He made an outstanding contribution to Germany v Holland in the second round when he analysed a spitting incident involving Frank Rijkaard and Rudi Voller, a scene which bespoke the terrible hatred which exists between these two nations. Using the magic pencil with which Giles would deconstruct a move, Dunphy drew a line from Rijkaard’s gob to Voller’s head, tracing the trajectory of the phlegm. Bill O’Herlihy watched indulgently, knowing he was in the presence of a master.

I was watching this in Smyth’s pub in Dun Laoghaire, where I would sometimes run into Donagh Deeney, the Furniture Removal Man in Juno whom you may remember from Mulligan’s of Manhattan, and Euro 88.

Ah, it was all coming together.

Germany won 2-1, confirming our suspicion that we had dodged another bullet there.

And the day after tomorrow, we would have the exceptional pleasure of watching England playing Cameroon, with the genuine prospect that the rampaging Africans would get a big, big result — shops in Dublin were selling out of Cameroon jerseys; we could feel it coming.

But the next day, it was Ireland v Romania in Genoa in the last 16 of the World Cup.

——

The International Bar, if it was so inclined, could probably claim that in the late 1980s it was the equivalent of McDaid’s in the 1950s — the pub of choice of creative individuals who would achieve renown in the fullness of time, or even posthumously, but who were just starting out back then, or struggling. And who could get their cheques cashed by the barman, because they weren’t particularly welcome in banks and because the amounts were usually small.

In fact, the reputation of McDaid’s is based mainly on its association with literary men such as Brendan Behan, Patrick Kavanagh, Flann O’Brien, Anthony Cronin, and J.P. Donleavy, whereas the International was a haven for all sorts. Virtually every Irish comedian of the time, several of whom became internationally successful, started out upstairs in the International. From Ardal O’Hanlon to Dylan Moran to Tommy Tiernan to Deirdre O’Kane to Kevin Gildea to Des Bishop to Barry Murphy, they would stand up in the Comedy Cellar and sit down afterwards in the main bar, which felt like a place of worship to the great god of alcohol, an altar. Or they would hide downstairs in the womb-like comfort of the basement lounge.

Conor McPherson put on some of his early work in the International. Members of the Rough Magic theatre company, such as Declan Hughes, the playwright and novelist and Lynne Parker, the director, were there or thereabouts. I remember Anne Enright, who was then working in RTÉ on the Nighthawks show, meeting Graham Linehan in the downstairs lounge to talk about something he had written or wanted to write for the programme, which itself was doing something different by being on RTÉ and being consistently funny, with Kevin McAleer in particular nailing the deep strangeness of Paddy’s eclectic cultural life.

And just in passing, Shay Healy’s Nighthawks interview with Sean Doherty brought down Charles J. Haughey.

——

Anne Enright would eventually win the Booker Prize and Graham Linehan would win BAFTA awards, though at the time, if you could have imagined such an astonishing thing, you might have assumed it would be the other way round — Enright, after all, was working in television at the time, while Linehan had not yet gone there, and seemed bright enough to write anything he wanted to write.

And so the International could claim that it provided all these talented young people with a University-of-Life education which enabled them to rule the world. Except it didn’t really feel like that.

In fact, the whole point of the International was that it was so unassuming, so lacking any of that bullshit. Most of the clientele and the performers upstairs would be dealing with Simon the Wicklow barman, a thoroughly sound man, a kindly individual from another age who cycled into work every day and who may have been the least arty-farty man in Ireland at that time. Apart perhaps from Matt, the other barman.

And though you could compile an impressive list of notable individuals who drank there, they weren’t all drinking there on the same nights, and many of them probably never believed they would go as far as they did — in fact for much of the 1980s most of them probably thought they were going nowhere. I don’t think that John Waters secretly saw himself selling about 40,000 copies of his first book, Jiving at the Crossroads and I doubt that Fiona Looney had an unspoken belief that her first play, Dandelions, would become one the most successful theatrical productions of all time in this country.

And did a later Hot Presser Peter Murphy imagine that he would write the novel John The Revelator, which would be described by Roddy Doyle as ‘like reading for the first time, almost as if I’d never read a novel before’?

I don’t think so.

There wouldn’t be enough drink in the world to make all that seem possible.

——

Looking back, it seems crazy that Conor McPherson could make that journey from lunchtime in the International to a run on Broadway. But as usual we must turn to football to give us a proper understanding of the nature of success on this scale and what it means. Because the breakthroughs of various individuals in the arts and show business were mirrored on a gigantic scale by the success of the Republic.

Whether these individuals would be inspired by the success of the football team, we can only guess — in fact, I know that Graham Linehan was almost totally uninspired by anything to do with football, and Arthur was funny long before we qualified for Euro 88 — but you could make a case that goes something like this: that breakthrough which the Republic made, which we thought would never happen until it actually did, gave everyone in Ireland an inkling of what success feels like, how exhilarating it can be. And because so many of us felt it and felt a part of it, we probably became more comfortable with the idea of success as a result, warily casting aside the culture of failure in which we had wallowed for so long.

In the years that followed, when we saw someone doing well for himself, even if we couldn’t relate to what he was doing, we knew how he felt, in some small way, because we had all been there, for a few moments, during Italia 90.

And we all understood, too, as never before, what a thin line it is between the crushing weight of disappointment and that surge of endorphins you get when you’re winning. Against Romania in the last 16, that line was so thin, there was nothing in it for ninety minutes and nothing in it for another half-hour of extra time and eventually there was nothing in it but a penalt

y kick.

——

It had to be the International, for this one, Liam and Arthur and George Byrne and I emerging again from the sanctuary of our homes to the relative sanctuary of our home away from home — it meant we could partake of the community spirit while still drawing solace from these so-familiar surroundings, sitting up at the marbled counter with the telly in the top right-hand corner where Gary Mackay had scored for Scotland, and with Simon manning the pumps.

The fact that we had a stool at the counter indicates that we got there early doors, to acclimatise, quite an achievement in itself on this day when no-one in Ireland was even pretending that a day’s work would be done. As if watching Ireland v Romania playing for a place in the quarter-final of the World Cup wasn’t work. And all the drinking that had to be done to make it even vaguely bearable could hardly be classed as anything but work, and essential work. There may have been a few people left in the country who regarded football at this level as a leisure pursuit, but for the overwhelming majority, until the result was known, this would be a day of agonising toil.

They were three or four deep at the bar of the International by kick-off, and those of us who were fortunate to have a seat were unfortunate in having to lift pints back through the crowd.

The match itself was a disgrace, another 90 minutes and another 30 minutes on top of that with almost no football being played, apart from the odd little spasm by the Romanians, who then seemed to concede that they were only codding themselves trying to play football against the likes of us. Even with the Berlin Wall down, those boys from Eastern Europe didn’t need much persuading that the cynical option was the best, that you might as well play for penalties if they’re offered to you.

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven