- Home

- Declan Lynch

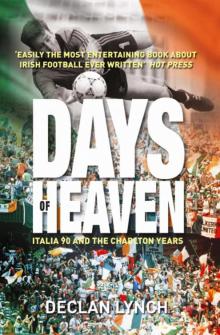

Days of Heaven Page 3

Days of Heaven Read online

Page 3

I was now working for a national newspaper — soon I would be working for two national newspapers and a national magazine. Yet it seemed quite normal to be renting not just the flat, but the television in the flat.

‘Confidence’, in Ireland at that time, was such a fragile thing.

Eoghan Corry, then Features Editor of the Irish Press, had asked me to write a TV column for the paper, making use of the rented TV (I think I bought the pen and paper outright). I would soon start contributing to the Sunday Independent and there was still Hot Press — in fact, I had interviewed Jack for that paper, early in the campaign for Euro 88.

I had been writing a sports column called ‘Foul Play’ in which we were placing football in a rock ’n’ roll context long before Nick Hornby and Fever Pitch. So an interview with Jack or with any football man would be a normal procedure, if indeed the word ‘normal’ could ever be used in relation to a Hot Press interview — for example, we used to actually print most of things that people said, rather than observing the ancient journalistic conventions of tidying up the bad language and the digressions and the loose talk in general. We did not feel that the people needed to be protected from such things.

The interview was done in the lounge of an airport hotel, with physio and batman Mick Byrne scurrying around organising room-keys and generally coming across like the PA to a busy executive. Indeed Jack laughed about the male-ness of the world in which he moved, expressing disappointment that I wasn’t a woman — Colette from Hot Press had organised the interview and he had been expecting her.

He seemed younger that day than we generally remember him. When he became a sort of Father of the Nation a few years later, he assumed an aura of seniority which obscured the fact that when he took the Ireland job in 1986, he was just 50.

For the first time, I noted that he kept getting names wrong: names of players, names of countries; he referred to Bulgaria as Romania and instinctively I was about to correct him, but stopped myself. If he didn’t know the difference by now, it didn’t matter. And while he was being factually inaccurate, he was not too far from the truth — for what difference was there really between Bulgaria and Romania? As Con Houlihan put it, these guys from behind the Iron Curtain who would come over to play football, were ultimately doing it for ‘the bit of freedom and some decent food’.

In fact, I don’t know what Colette had said to him, but Jack was ready to talk about environmental issues, too, which I felt at the time was surprisingly generous to a magazine that he’d probably never heard of, and about which Mick Byrne, with his local knowledge, might have had some legitimate concerns.

He spoke with passion about various fish-kills which were happening at that time. Fish-kills were big in Ireland in the 1980s, most of them caused by farmers releasing vast quantities of slurry into rivers and lakes which were once pristine fishing grounds but which were now destroyed. He argued that farmers found guilty of such hooliganism should have the land taken away from them.

Naturally, I would write up this interview in longhand, on sheets of foolscap. Because we wrote such long interviews at Hot Press and because most of us were little more than children, our typing skills hadn’t developed to a stage where we could rattle off 3,000 words to deadline. In fact, the practice of writing in longhand would remain with me for many years, almost until the turn of the century, even when I had learned to type properly — I had become so used to thinking in longhand, I felt that a piece always read a bit better if I wrote it up first and then typed it.

To recall the methods we used at the time at what we assumed to be the cutting edge of the media, is to realise that despite our modern notions about getting football managers from England and the like, we were still not far removed from medieval ways.

When I first started writing for the Irish Press and then the Sunday Independent, where typed copy was a minimum requirement, Jane would do the typing for me and I would carry the precious sheets down to the DART. I would read through them on the train, crossing things out and adding things in with a biro. I would hand this attractive offering to Anne Harris in the Indo, or to Eoghan Corry at the Press.

I didn’t say ‘in’ the Press, because I would always meet Eoghan, who was one of the gentlemen of the game, in Mulligan’s of Poolbeg Street. I would have a pint of Fürstenberg and he might have a pint of Guinness, and he would read my article there in the pub and hopefully at some point he would start laughing or otherwise indicate his approval. Then Eoghan would take my copy up to the office and he would be gone for a while, editing his features. But soon he would return and we would have a few more pints of Fürstenberg and maybe a few more pints of Guinness and a few more laughs.

It seems now that the newspaper business in Ireland was run amid a veritable Niagara of alcohol. An angry reader once wrote to Eoghan complaining about something in the Irish Press which had annoyed him, giving an address which indicated that he was an inmate of a mental institution. In fact he stated in his letter, ‘As you can see from my address, I am mentally disturbed’.

Eoghan wrote back to him, under the Irish Press letterhead, with the opening line: ‘As you can see from our address, we, too, are mentally disturbed.’

And yet, fantastically, it seemed to work. Two newspapers a day and a third on Sunday somehow emerged from Burgh Quay, along with a lot of interesting people of the kind that you don’t find any more in ‘the media’, in these good-living times. To quote Houlihan again, the modern newspaper office has all the atmosphere of a suburban pharmacy.

Not only were they interesting, as I look back on it, but I marvel at the general levels of kindness and understanding which these highly experienced professionals displayed towards the likes of me, arriving into their world without their ancient skills such as shorthand, and without much intention of learning it either.

And we didn’t have a phone in the flat. The phone was in the hall, one of the old black pay-phones, with Button A and Button B on it. Jane and I and Roseanne were at the back and the hall was round the front, so you would hear it ringing in the distance and if no-one had answered it after three or four rings, this would mean that Liam wasn’t in, and if it kept ringing, it meant that other tenants such as Pat McManus, the lead guitarist with the heavy metal band Mama’s Boys, weren’t in either. At which point you would run like hell to answer it, out the back and round the front.

Astonishing though it now seems, while journalists at the time were inclined to chide Jack for his supposed lack of tactical sophistication, we didn’t regard it as abnormal to be living in flats with no phones.

Perhaps the defining narrative of the phone-in-the-hall era concerns an interview with Keith Richards which was due to be conducted by Liam Fay of Hot Press, over the phone, with Liam at his flat in Rathmines and Keith at his home in the Caribbean.

Except Keith’s people obviously wouldn’t be giving the private Caribbean phone number of a member of the Rolling Stones to some Paddy rock journalist. So it was arranged that Keith would be given Liam Fay’s number, which he would call at 7.30 in the evening.

But Liam didn’t have a phone in the flat.

The phone was in the hall.

So it was, that one evening at around 7 o’clock in a large old house in Rathmines, Liam Fay knocked on the door of every tenant in the building and asked them if they could do him a favour and avoid using the phone at around 7.30, because he was expecting a call from Keith Richards in the Caribbean.

——

So in my mid-twenties, while I seemed to have something resembling a career, even a life, it would not have crossed my mind that this might be the time to do something mad like get a mortgage and live in an actual house of our own. We had a powerful stereo and a fine record collection and some very good books and we could always do the Lotto, which had just started. So we didn’t feel the need to be borrowing, say, 50 grand, to get on the ‘property ladder’.

Most of us who came of age during the 1980s were similarly indifferent to the long

term, just happy enough to get through the week with the rent paid. And most of the people I knew just drank too much to be annoying themselves with property ladders and the like. We were already angry enough, about things like divorce and contraception and abortion, not because we cared much for these things in themselves, but because they were the issues in the moral civil war being fought in Ireland, which Jack may not have noticed in his zeal to show us how to win football matches, but which was still festering.

Not that it’s necessarily a bad thing, to be angry, if you’re working in journalism. It was probably what brought many of us into it in the first place, this idea that there was an old Ireland to be defeated, as quickly and as completely as we could manage it, to break through the delusions which had sustained that old Ireland, the lies which were just too big, even for Paddy.

When people enter ‘the media’ now, they have all sorts of fine ambitions to review restaurants for the Irish Times, or to write a wine column for the Sunday Business Post, or to present the weather on TV3. For us, presenting the weather was an impossible dream — at least until Ireland was free. Living in Dun Laoghaire, for example, it would occur to me, as I watched the boat leaving for Holyhead every day, that roughly ten of the passengers on board must be women heading off to get an abortion. Given that 3,000 women at the very least were doing this each year, and that, pre-Ryanair, most of them would get the boat, you just did the math.

But there was no abortion in Ireland, so that was all right. We were not like the others, who permitted the slaughter of the innocents.

Though of course we were like the others, we just pretended that we weren’t, out-sourcing our abortions for decades, the way we had out-sourced anything else we couldn’t handle, to England.

It was these fantastic feats of self-deception that were being challenged at the time. It was nominally about these great moral issues, but it was ultimately about Paddy trying to blast through some of the bullshit, the terrible, terrible bullshit in which he had been standing up to his neck for generations.

So while the 1980s were a hateful time in many ways, they may eventually be viewed in a kinder light, as bullshit’s last stand.

A certain kind of bullshit, at least.

Ultimately, we would still have ample quantities of it knocking around, and varieties yet to be discovered. It is a national addiction, which can manifest itself in many ways. And of course it is not unrelated to our primary addiction, the same then, as it is now, and which unites so many of us in alcoholic fellowship, wandering unsteadily to the beat of the same drum.

So when a load of cant by Bishop Brendan Comiskey appeared in a Church publication, accusing me of blasphemy in relation to something I had written in the Irish Press, it merely confirmed to me that people like him were the enemy and that they must be done down.

We had just about reached the stage when a ‘blasphemer’ wouldn’t lose his job and have to leave the country after being set upon by a bishop, and soon Bishop Eamon Casey would be doing his own bit to advance the liberal agenda. But I still could have done without Comiskey’s ambush over one line that I hadn’t even intended to be blasphemous — and anyway, it wasn’t much of a line, something about Madonna the singer possibly having a child, who will hopefully give her less trouble than the original Madonna had with her child.

I would condemn myself for heavy-handedness and for the all-round lameness of that effort and I ask God’s forgiveness for that. Nuala O’Faolain defended me in the Irish Times, mercifully declaring that she wouldn’t mention the offending line because it was so innocuous, sparing both the zealots and myself a lot of grief.

It took me a long time to realise that Comiskey and I may have had our differences over some minor matters of theology, but that in relation to the one true faith — the beer — we were more or less ad idem. Comiskey was eventually treated for alcoholism, though at the time, when there was not even a mild suspicion about his weakness for the jar, he would have been regarded as one of the more able administrators in Ireland, with newspaper profiles suggesting that if he hadn’t gone for the priesthood, he would have undoubtedly become one of our more progressive business leaders.

——

Our best and best-loved footballer, Paul McGrath, would also eventually be treated for alcoholism, though at the time, we were only worried about his knees. It would become a national euphemism, Paul McGrath’s knees, somewhat complicated by the fact that he really had a problem with his knees, but that problem tended to be aggravated by his drinking. In fact, Paul was drinking steadily — and so was I — on the night we agreed that I would write his biography.

Alcoholism, they say, is a ‘progressive’ disease. Along the way there are mysterious lines that you cross without knowing it, which only start to become clear to you when it is all over — if it is all over. If you could measure it on a scale of one to ten, on the night that I agreed to write Paul McGrath’s biography, in the run-up to Euro 88, I was probably at about six. By the end of the Charlton era, I would be up there at about eight-and-a-half, pushing nine, and in truth, I probably never went beyond that — you don’t need to, really.

Where was Big Paul at? Only he knows, and maybe he still can’t quite work it out.

But it was quite a night, all the same.

The Boys In Green, as they were now increasingly known, were down in Windmill Lane Studios recording the track ‘The Boys In Green’, which would be their anthem for Germany, and which was written by a gentleman of the press, the late Mick Carwood.

We are the Boys in Green

The best you’ve ever seen

We’ve just made history-ee

We’re off to German-ee

We’ve had to wait till now

Big Jack has shown us how

You’ll wonder where we’ve been

When you see the Boys in Green

And you’ll say Ireland, Ireland, show them what we’ve got

Ireland, Ireland we can beat this lot

Ireland, Ireland we can celebrate

Ireland, Ireland in Euro 88

——

We should pause here and try to imagine an English football journalist contributing to the England cause in this fashion, and try though we might, we just can’t see it.

His song was produced on that Sunday afternoon in Windmill Lane by Paul Brady and featured many of the Boys themselves, who sang heartily all the way through, observed by other gentlemen of the press including myself, Mr George Byrne and Mr Eamon Carr.

I recall talking at length to Chris Hughton, about how he, a black man, had always regarded himself as Irish. He seemed patently sincere and he had nothing to prove in that regard anyway, since he had been a black man playing for Ireland back in the days when we only had about five black men in the entire country — and by 1988 that number hadn’t increased to any noticeable extent.

Indeed George Byrne happened to be on a trip to Detroit around that time, with friends, and the taxi-driver, learning they were from Ireland, asked them how many of ‘the brothers’ were in Ireland. And they started going through them ... ‘there’s Paul McGrath ... and Philo, of course, but he’s dead now ... and Kevin Sharkey ... and Dave Murphy ... and ... and that guy who plays the guitar outside Bewleys ...’

The taxi-driver interjected. ‘That many, huh?’

But one of them was Paul McGrath, after all, who contained multitudes.

When the recording party repaired to the Dockers pub next door to Windmill, Eamon Carr and George Byrne and I found ourselves in the corner of the lounge, drinking with Paul and his companion, John Anderson, of Newcastle Utd and Ireland. It was Eamon that Paul really wanted to talk to, Eamon being a bona fide Irish rock legend from his time with Horslips. I myself probably would not have been sitting there if it wasn’t for the same Horslips and the life-changing effect that they had had on me and on a fair few others like me in ‘rural Ireland’, lonely boys, out on the weekend.

We lived only for their all-too-infrequent

visits. They were magical, extraordinary, these five men, who were able to demonstrate that you could be playing the dancehalls like a thousand other Irish bands and yet somehow not be bad.

That you could write your own songs, and they would not be bad.

That you could put on a show and it would not be bad, but would have wondrous things like a proper PA system and a mixing desk and actual roadies darting around the stage, plugging in guitars which, when played, would not be bad.

Eamon was one of my heroes, too.

And as the talk inevitably turned to Ireland and the state that she was in, Paul was getting stuck in to his own upbringing, how Ireland had treated him, and soon there was a fine and righteous anger around that table.

I had only encountered Paul once before that, when I had been coming out of the International Bar and had almost run into him and a woman with whom he seemed to be arguing. You’d never hear him giving interviews.

So this was the first time I realised what an articulate fellow he was, how well he seemed to understand the things that he had seen. And as the pint pots stacked up in the Dockers, he said that he wanted to put all this stuff in a book, all this shocking stuff.

Thus, for a couple of hours one night long ago in the Dockers pub, I became Paul McGrath’s official biographer.

He meant it, and I meant it.

We meant it with all our hearts.

Our agreement was witnessed by a distinguished if controversial rock journalist and a genuine Irish rock legend, so it was sound.

Days of Heaven

Days of Heaven